JOY

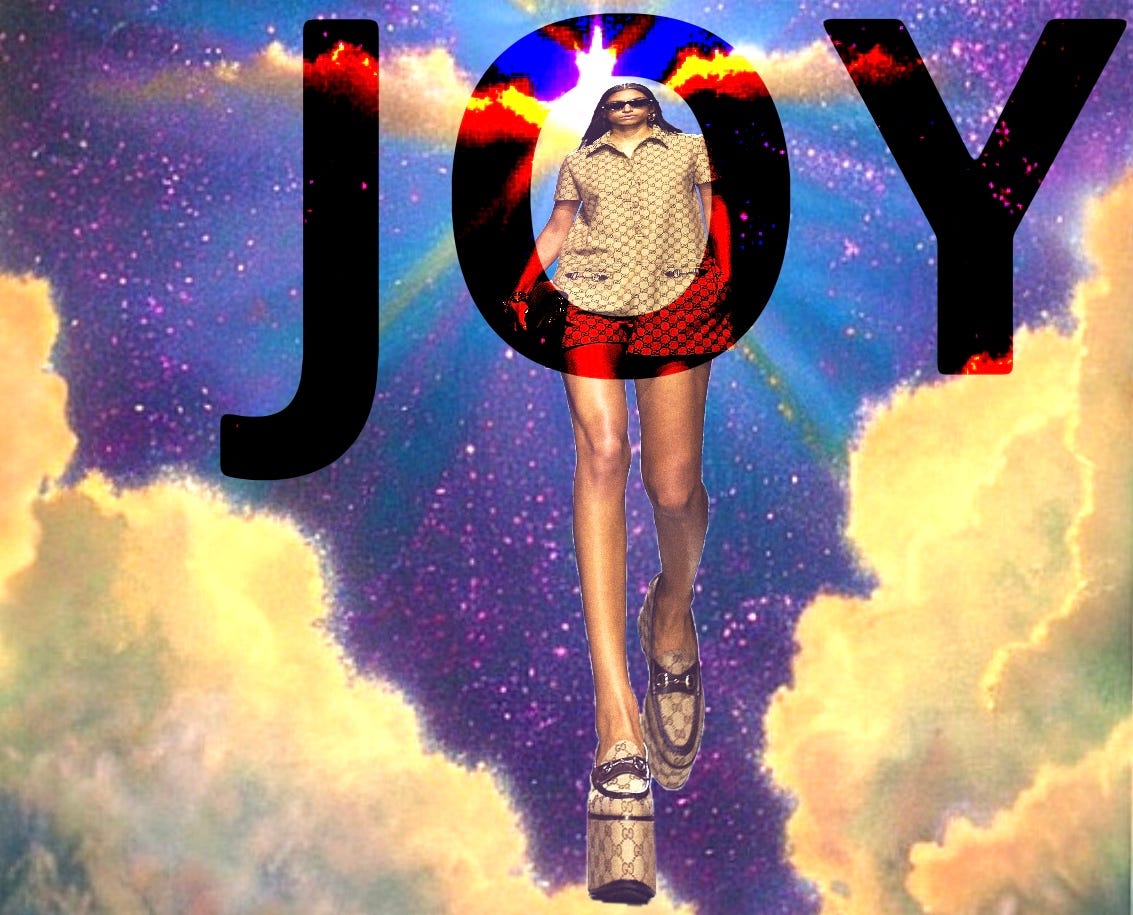

Do we have a new trend? The joyfication of fashion.

Has joy become a commodity, something to be bought, traded, measured and applied like an Instagram filter? A few days ago, when Gucci's new creative director Sabato de Sarno finally unveiled his first collection, fashion journalist

commented on Instagram and on her fantastic Substack that both the show and the collection's photobook, Prospettive 1 Milano Ancora, which Sabato de Sarno says is Gucci's way of "returning to a sense of fun and joy" actually seemed to be at the antipodes of those emotions.So, how did words such as Fun and Joy become a vehicle to market goods whether or not they make any sense within the material being presented? These concepts are as old publicity tools as publicity itself. But there’s very little that can be considered joyful or even fun in Gucci’s new collection, and judging by the selection of images from the book on Hypebeast, the same can be said of it. Personally, I did like the little I saw, the photography is evocative, sophisticated and very dark, but I felt for the art director; if joy and fun were the brief, nobody bothered to send them the memo. If you’re making a collection that’s minimalist, dark and sophisticated, why not call it that? Where did this idea of fun come from? Maybe the fun concept was pushed by Kering’s executives, who were the ones not having any after Michele’s latest collections ended up selling less than expected, albeit still, plenty more than when he took the helm at the house.

This week, I have been thinking a lot about how this is becoming a thing, which I’d like to call The Joyfication of Fashion, similar to greenwashing, but with happiness instead. According to Vogue Bussiness: The collection was titled “Ancora” (again, or encore in English), a word chosen by De Sarno to convey the idea of a desire “that you still have, but you want more of it because it makes you happy” Let’s stop here for a moment.

As with Pharrell’s Louis Vuitton Men’s collection, where the choir sang for their lives about unspeakable joy, (the show gave many things, but I couldn’t find that sense of joy anywhere else except the singing) it seems to me that joy is the new word saving the day for fashion brands on a mission to sell to Satan himself and hopefully, in huge numbers. In Pharrell’s case, the collection was correct and desirable, the man has great vibes and he is definitely very cool and interesting, but joy is another matter. LV wants to keep the spirit that Virgil Abloh awakened with his work, fully steeped in childhood dreams come true, which managed to convey an authentic feeling of joy. But this wasn’t a manufactured idea then, as much as it slightly was with Pharrell’s mise en scène.

A similar thing happened with Gucci’s new debut collection, wanting more and more without an end used to be known as consumerism -a word which fits here like a glove- but is now called Ancora. On the other hand, Joyful seemed off track as the right word, Commercial or Profitable would be more appropriate. And coming from Michele’s universe, which had -as in Abloh’s case- such a true sense of fun and diversity, this one felt even more depressing. Don’t get me wrong, the collection is going to sell like hotcakes; it is sophisticated, elegant, elevated and quite gorgeous if we don’t look at the shoes or the fact that the casting directors were brought in straight from the 00s with a time machine. I am sorry Sabato, I agree with Amy Odell, this collection is not giving joy, let alone fun.

But anyway, my point here has to do with the idea of Joy as an emotion related to clothes or the personas they communicate. I got into this career because it gave me joy (admittedly I thought it’d be more often than it has been), and I love the force that fashion can be at constructing universes and validating alternative ideas or ways of being. As consumers, we project into our clothes to feel exactly that; an outfit or a piece of clothing can articulate our sense of acceptance or pride, bring back a memory from a happy moment or person, or make us feel invincible and transformed. Here are two favourite examples of mine when it comes to understanding how fashion can create joy:

One is the documentary Paris is Burning, which records how the trans community in 1980s New York felt validated, empowered and seen through the outfits they wore to the balls. The other is this great TED talk by Dr Christine Checinska (Lead Curator for Africa Fashion at the V&A Museum) on disobedient dress, in which she talks about fashion’s potential to transform and how it can open a way against invisibility and stereotyping, the force that her golden shoes have to create a joyful shield for her is universal. We all know the feeling and have items in our wardrobes or at least in our memories that embody the promise of our better selves. And those pieces do evoke joy, but it’s the wearer who invests that power in the piece of clothing, not the brand.

The collections and shows by Virgil Abloh and Alessandro Michele gave us joy because we felt a strong emotional connection with their narratives, which had less to do with buying ourselves senseless and more with the unifying experience of being human and full of potential. Both creative directors managed to express in their own personal way that moment where aspirational meant that everything is possible without self-consciousness or second-guessing ourselves. If that sold a million bags and loafers along the way, then better yet. Can these brands change radically to fit new sensitivities or consumer trends, and keep the spark along the way? Since the sole goal is profit, having a creative director who can conjure joy is a matter of pure luck, not something that can be measured, manufactured and packed with a ribbon for the customer to acquire.

When a brand tries to slap joy as a label over its wares, the whole experience shifts, and things like aspirational consumption, and manufactured status take centre stage, to better or worse results depending on how the public perceives the brand’s intentions. Both brands I’ve mentioned here can be understood for trying too hard to keep their cake and eating it. I wonder though, if this is something we’re going to keep seeing. Personally, as an unruly creative and consumer, I cringe at the idea of going back to a pre-aughts style of shameless marketing codes of “buy more to feel good”, I would rather not have to make those campaigns, and I certainly don’t want to buy things from a place of emptiness, but isn’t that why consumption happens in the first place? Aren’t we all trying to fill a void or feel joy through our possessions and choices? And aren’t we as creatives tapping into those subconscious needs to sell more stuff? Is that the only way in which it can be done? I leave the answers to you, dear misfits. I read you in the comments.

Happy weekend,

Patty