Link a la versión en español al final del texto.

What is the first thing that comes to your mind when thinking about shape? Do you maybe think of the silhouette of a lover, a piece of fruit, a favourite lamp or sofa? Perhaps you remember a sculpture you saw recently? Do you think about a dress, your car?

Shape means form, but it also means to give form, or to receive it, as in something or someone having an effect on another person, changing part or all of them forever. It can refer to an actual silhouette, or to a physical or emotional state. It is a word that defines things and people in so many ways that it is a whole subject in itself.

The idea of using words to guide each essay came from a chapter on Basquiat in Olivia Laing’s book, Funny Weather, it is a collection of her articles and essays on artists and their lives. In it, she numbered a series of words that often appeared in his work and were part of his discourse and his life:

So, out of curiosity, I started writing my own alphabet. I was surprised by the words that came out, from noodles to journey to understanding or hair dye. Shape was the first word that I wrote, I guess because I was thinking about the shape of my life, what it looks like, and how it got to be like that in the first place.

What are the things that come to my mind when I think about shape? The first and most intimate is my own physical form. At times in my life I’ve had a hard time accepting my body and the way it looks, full disclosure:

I've cringed looking at my legs, I have mixed feelings about my belly and have lived emotionally removed from my boobs for years. These feelings come and go, they don't define how I perceive myself or my beauty but they are there. I grew up with a mother who struggled with her own body and a very beautiful grandmother (my dad’s mum) who believed that by criticising me -and everyone else- we could correct ourselves into a better version (as if by sheer force of will or shame). Objectively speaking, I am a woman in my 40s who has never gone beyond a size 38 and has never had any real weight issues. I’m fully aware of my privilege and feel silly for being so ambivalent about the body I live in. So yes, body dysmorphia is an issue. I deeply love and respect the journeys and challenges these two women in my life have had to live through, but I have rebelled against the ideas I absorbed from their own traumas with all my might, sometimes succeeding, sometimes being swept away by the tide.

Then I chose fashion as a career, where all of this internalised trauma lingers on the corners of every single day. Because the idea of Shape is at the heart of fashion and it’s entangled with each one of its areas, shape in terms of silhouette is one of the most important aspects of a garment or an outfit, but the shapes and silhouettes that come in and out of fashion also have an impact on the way people feel about themselves, let alone how much those silhouettes actually shape the world around them and vice versa. The issue of fitting in, I’ve discussed already.

As a stylist and fashion editor I often think about the message I'm putting out there; the thing with fashion images is that they are designed for the viewer to step into the picture and become one with the model. So in my work, one of my thoughts is the way clothes fall on bodies, the other is the people I want to represent. Are they perfectly unattainable models of beauty, intelligence, grace, coolness… or are they closer to the parts of us that remain hidden and waiting to be unleashed, like the rebel, the poet, the weirdo, the unreasonable or the wild? I do want the latter to be at the forefront, to be fiercely represented but haven’t always managed, because my bias and traumas come with me wherever I go. Deep down, I am conditioned to be comfortable when things feel orderly, repetitive: normal (argh!). We all are.

In general, our ideas about shape are often related to balance and harmony, partly due to the Greco-Roman model, but actually, for statues to appear proportionate to the viewer (usually looking from below), heads and other parts of the body are often distorted from a frontal perspective. In the case of humans, family and society shape us so that we are presentable, but this will certainly distort some parts of us. Is there a way for these conventions to be passed on to us without harm? Probably not, because shaping also means building up or creating, that is, changing the nature of something or someone to make it fit for something else.

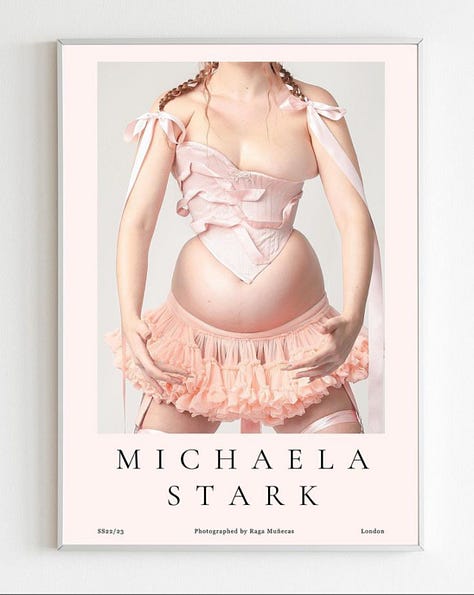

Then there's the question of beauty. After all this shaping and moulding, our beliefs into what can be considered aesthetically pleasing are not so much our own as they are prefabricated concepts, passed down through generations, representing more faithfully the normative way of understanding beauty than whether or not something is actually, objectively beautiful. Don't believe me? Let me show you the work of an artist that challenges all those conventions, confronting us right at the centre of our fears or body issues or both. Meet artist and designer Michaela Stark.

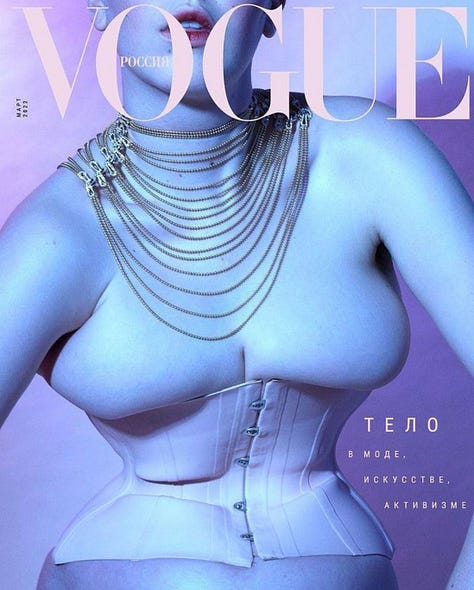

Michaela Stark is a couture artist who designs lingerie that, in her own words, “explores the territory between the beautiful and the grotesque”. The delicately intricate pieces she creates push, cinch and mould the body away from all those conventions I was talking about before, transforming it into a work of art that demolishes every notion of shape and beauty that reigns unchallenged in our psyches.

Her work is not about body positivity per se, but it is, because her investigation is as refreshing and liberating as much as the body is tucked in and out in highly unusual ways. It is a celebration, a break away from our insecurities, through her exploration of the binary within our idea of beauty. Shaping in this way a body that looks impossibly beautiful and unrecognizable.

No wonder, she is one of the artists chosen by Victoria’s Secret to feature in the new season film that will be released later this month and represents the brand's efforts to become relevant for the present day and its full rebranding. Her work speaks to a generation that has grown weary of and reject society’s imposed notions of beauty, allowing them to love themselves where society couldn’t.